Faculties struggling with four-year contracts for temporary teachers

At the end of 2018, the Executive Board (CvB) and the deans made new agreements about the contracts for temporary teachers. From 2019 onwards, 80 percent of temporary teachers would have to have an employment contract of at least four years and 3,5 working days per week (0.7 FTEs).

With such a 'robust' contract, the University wants to be perceived as a better employer -- temporary teachers often get contracts for a shorter amount of time or less working days per week, which creates uncertainty about income and career progression. In addition, the Executive Board hopes to reduce the workload for current staff by reducing the number of new colleagues that need to be recruited.

However, this spring, it turned out that only 20 percent of the teachers hired in 2019 had a ‘robust’ contract. Almost 50 percent of the new colleagues have contracts in which neither condition has been met. The remaining teachers have been given contracts meeting only one of the conditions. It is a thorn in the side of the Executive Board that faculties do not adhere to the guidelines they have signed up to, which is why they sat down with the deans again right before the summer.

Percentage of UU workers hired from 2019 onwards, per contract duration and full-time contracts (FTE). Red: less than 0.7 FTE and less than four years; Yellow: less than 0.7 FTE and more than four years; Orange: More than 0.7 FTE but less than four years; Green: More than 0.7 FTE and less than four years.

They agreed that all faculties will review the contracts of the new teachers. If possible, an extension will be provided to teachers whose contracts do not meet the new UU definition of a temporary contract. According to the Labour Market Balancing Act – also known as the new 'flex law' – an extension is only possible if the contract has never been extended before. "This is a solid measure that we are taking along with the faculties, because we see that the percentage is still too low," said Anton Pijpers, President of Utrecht University, in the University Council Committee on Finance, Personnel and ICT. "Last year I thought this could be implemented quickly. I am disappointed.”

Teachers don't always want a robust contract

Four faculties have many temporary teachers on their payroll (see box at the end of the article). The Faculties of Law, Economics, and Governance (Rebo), Social Sciences, and Humanities are the ones most in need of stepping up their efforts to increase the number of robust contracts. These are faculties with many students and a variable turnover. Even though the deans of these faculties support the University's new policy in theory, in practice they say they’re faced with obstacles that make it difficult to give every new temporary teacher a robust contract.

Marcel van Aken, dean of the Faculty of Social Sciences, highlights one of the reasons why some teachers do not want a 0.7 FTE-contract: "Our clinically oriented programmes employ teachers who have a job at a mental healthcare institution for, say, three or four days a week and only lecture with us one day a week. They don't even want a 3.5-day contract. But we don't want to lose them either, because their practical experience adds value to the programme.” The faculty does, however, want to investigate how many teachers of this type are desirable. "You have to find a balance. With too many teachers holding a small contract, you get a fragmented whole.”

Rebo and Humanities also employ teachers who have other jobs. In addition, a 0.7 FTE appointment can be a problem for those who do not have another job on the side. "Even though there are teachers without a second job, some of them still don’t want a 0.7 FTE contract.”

A German teacher cannot teach Italian

At Humanities and the Faculty of Law, Economics and Governance there isn’t always suitable work to justify a 3.5-day contract. Dean Algra: "The Executive Board may want new teachers to be broadly deployable, but this is not always possible at our faculty. In some cases, you can ask a History teacher to lead a first-year working group on a different period of time or a somewhat different subject from the one he specialises in, but I find it difficult to get a German teacher to teach Italian or a Celtic teacher to teach an Art History subject. In small courses there is often just not enough work for a 0.7 appointment.”

Janneke Plantenga, Dean of the Faculty of Law, Economics and Governance shares the view that not every teacher is broadly employable: "Some of our teachers teach one part of the law and are not easily employable for another course.” If teachers can already be broadly deployed, it requires a different organisational structure, she says. "At the moment, temporary teachers are usually sought out and hired at a fairly low level within the organisation. One department does not check whether the other department may have a vacancy. This would require looking at vacancies at higher level, such as that of the education director. Then you can see whether one teacher can be hired for different subjects, someone who is more of a generalist.” This change is currently being implemented at the Faculty of Law, Economics and Governance. "But it takes time," says Plantenga.

Humanities scholar Algra also has a hard time believing that teachers will be broadly deployable. "The Executive Board may play a little too fast and loose. We offer 21 Bachelor's and 18 Master's programmes. I want to offer students a professional education, which includes teachers who know what they are talking about.”

Financial risk if student numbers decline

Faculties are sometimes reluctant to offer robust contracts for financial reasons. For a not-so-rich faculty such as Humanities, robust contracts are a financial risk, Algra says. "Two years ago we suddenly got a lot more Artificial Intelligence students, so we took on extra teachers for that. We didn't know whether all these students would move on to the second year and complete the entire programme. We have programmes that are growing and shrinking and programmes that are fluctuating. You don't want to give someone a four-year contract if there is no more work for that teacher in two years' time.”

The financial risk also plays a role at the Faculty of Law, Economics and Governance. "At the Law programme they added 60 percent more first-year students to the Bachelor's programme this year. We had 650 and now there are more than 1000. While it's good that the programme is doing well, the question is whether all these students will be completing their studies. This is, of course, a strange year because of Corona. There are probably some first-year students who would have preferred to go backpacking in Australia this year, but have started studying anyway. Will they continue their studies or not? From a management point of view, it is very risky to offer all new teachers a four-year contract.”

Another point that generates cold feet is that the probationary period for a temporary contract is only two months. Plantenga: "If you hire a teacher for one year, you can then extend the contract by two years if the teacher is satisfactory. But what does it mean for education if the teacher is given a four-year contract and after the two-month probationary period it turns out that he or she is not suitable?”

Social Sciences is another faculty concerned with the possible financial consequences of a four year-contract: "Programmes are used to budgeting in the short term and adapting to the influx of students. They are afraid of encountering financial problems if the intake decreases. They have to get used to the new rules. As Faculty Board, we have said that we guarantee any financial setbacks at the educational level.”

Faculties review all contracts

In the meantime, the faculties have begun to review all contracts, adjusting then when possible. The percentage of robust contracts is already increasing, according to the deans. They will report to the Executive Board in November about the contracts that cannot be extended.

According to dean Van Aken, all departments and programmes of Social Sciences are now aware that new teachers will receive a robust contract. They must report to the Faculty Board when offering such a contract is not possible. Van Aken sees that everyone in his faculty is doing their best to increase the percentage. They’re also seeking “more complete teacher” who can be deployed more widely, but “the need for teachers who work in the field remains as well.”

The percentage of robust contracts is also rising slightly in the Humanities. "We’re opening the contracts where we can. We are on top of it", says Algra. With every new vacancy, the faculty checks whether the offered job is robust enough. But will the Humanities reach 80 percent this year? "We are really trying, but we are not going to make it. Our reality is different, I don't even think we will reach 70 percent.”

Janneke Plantenga, of the Faculty of Law, Economics and Governance thinks her faculty should perform better: "But 80 percent is a challenge. Apart from the strongly fluctuating student numbers and our strive towards quality education, there’s always what we call the 'peak and sick’: the moments when we need teachers to help out in case of sudden increase in workload or a colleague’s illness.”

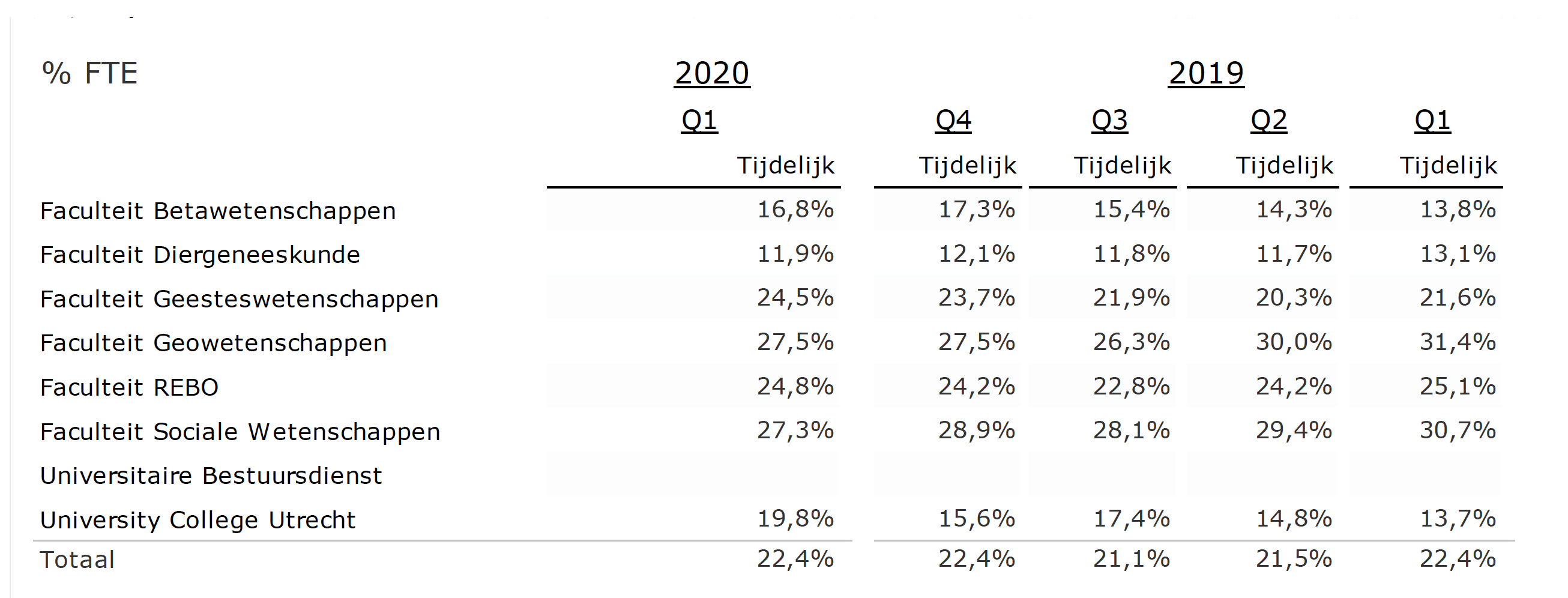

This table shows that not only Humanities, Social Sciences, and Law, Economics, and Governance employed a large percentage of temporary teachers in the first quarter of 2020. The Faculty of Geosciences has the highest percentage of temporary teachers. So why doesn't this faculty need to go the extra mile?

Dean Wilco Hazeleger admits that "things do not seem to be going so well for Geo in this regard.” But part of the explanation lies in the method of registration. "In the past, we gave temporary teachers-4 an appointment for two years, followed by another two-year contract. In 2019, we immediately gave all current teachers an extension to four years with a minimum of 0.7 FTEs. But this is not registered by the staff system as a robust four-year contract.” Hazeleger says that all new temporary teachers-4 will immediately be given a four-year contract from the end of 2019.

A second reason is that the percentage of temporary contracts also includes so-called tenure track teachers who were previously also given a two-year contract with a two-year extension thereafter. A tenure tracker works towards a permanent job as an assistant professor, associate professor, or professor. They are also seen as temporary staff in the personnel system. Since the end of 2019, this type of teacher at Geosciences will immediately be appointed for six years, which is seen as a permanent contract in the reports.