Assessment framework for the fossil fuel industry

New fossil fuel collaborations possible after Executive Board watered down advice

At the beginning of this year, it emerged that the new assessment framework for collaboration with the fossil fuel industry still allows new partnerships with these companies.

This means that Utrecht University (UU) is not honouring its agreement made two years ago. At that time, it promised not to enter into any new partnerships with fossil fuel companies and organisations that are not intensively and demonstrably committed to accelerating the energy transition, in line with the Paris Climate Agreement. In this agreement, various countries, including the Netherlands, committed to limiting global warming to 1.5 degrees, but no more than 2 degrees.

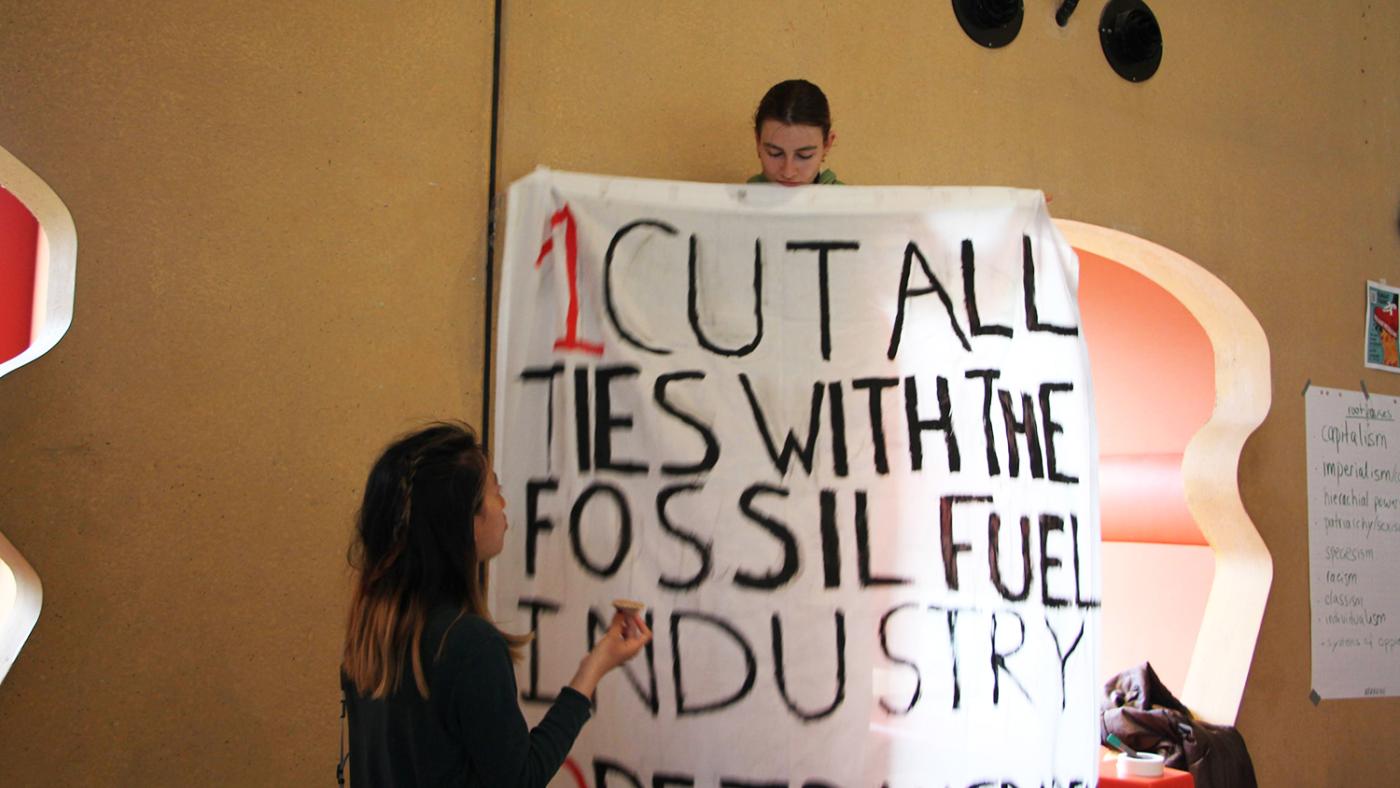

In March 2023, the Executive Board held discussions with the university community during two Deep Democracy sessions. The meetings were organised because an increasing number of students and staff were speaking out against UU's collaboration with fossil fuel companies. The discussions were intended to help the university board reach a position on the matter. Under pressure from climate activists who occupied the Minnaert building in May of that year, the university board decided not to enter into any new partnerships with fossil fuel companies that do not comply with the climate agreement.

Exceptions

However, the new assessment framework (only with solis-id) makes a number of exceptions, which means that there is still room for new partnerships with the fossil fuel industry in the coming years. For example, new projects in existing consortia do not need to be assessed. A number of these consortia will continue until 2030 or 2033.

In addition, scientists who still wish to enter into a new partnership with a fossil fuel company can submit their research proposal to a special assessment committee for collaborations with the fossil fuel industry the next five years. This committee will assess, among other things, whether the research contributes to the energy and materials transition.

The UU's list of fossil fuel collaborations shows that 16 of the 26 collaborations take place in consortia. These consist of knowledge institutions and companies that conduct joint research. Almost half of the partnerships will expire this year or next, but two will be completed in 2030. The GroenvermogenNL project of the government's National Growth Fund will run until 2033. As long as the consortia exist, new research may be started within them in accordance with the review framework.

Criticism of expert group

The action group Scientists for Future (S4F) considers the new assessment framework to be far too weak. It points the finger at the expert group that drew up the assessment framework. According to S4F there is a conflict of interest because four of the eight scientists in the expert group collaborate or have collaborated in the past with the fossil fuel industry. They have an interest in weakening the assessment framework, says Guus Dix of S4F and sociologist at the University of Twente: “Half of the expert group may not want to stop collaborating with the fossil fuel industry at all, because this affects their education and research. It would have been better if the UU had avoided any appearance of a conflict of interest.”

Executive Board weakened advice

However, the eight-member expert group points to the university board. It watered down the advice, says Judith van Erp, chair of the expert group and professor of Regulatory Governance. “In our group there was no discussion about whether we still want to collaborate with the fossil fuel industry. It was clear to everyone that the collaboration is problematic, including those who have worked with the fossil fuel industry in the past.”

The expert group was tasked with specifying what is meant by “fossil fuel industry”, to which forms of collaboration the framework applies and how it can be determined whether companies are complying with the Paris Climate Agreement.

“Two major changes were made to the framework we recommended to the Executive Board”, says Van Erp. This happened after the university board asked all deans for advice on the expert group's assessment framework. As a result, existing consortia were excluded from the framework. “The extension of existing collaborations and new projects in existing consortia that require a new contract will not be assessed after the change. This means that far fewer collaborations will be submitted to a critical assessment committee and there will still be room for collaboration with the fossil fuel industry.”

An assessment committee is currently being set up to assess new collaborations using the assessment framework. Over the next five years, scientists will be able to submit their research proposals to this committee, provided that the research contributes to the energy and materials transition. However, future partners will be subject to a less stringent assessment than that proposed by the expert group that developed the framework.

"We also wanted a light partner assessment. Partners who do not yet comply with the Paris Agreement had to show positive development. That criterion no longer applies to consortia in which the fossil fuel industry contributes less than 25 percent of the funding. In addition, we had said that researchers had to explore demonstrably more sustainable partners. This has been changed to a reasonable effort, which can be achieved quickly.‘

Strategic considerations

In a written response, the Executive Board says it fully supports the composition of the expert group. “A conscious decision was made to also include scientists who have experience in research collaborations with the fossil fuel industry in this expert group. This is because the Executive Board believed that you cannot draw up a framework for collaborations with the fossil fuel industry without involving people who have experience with this type of collaboration.” The board considers it “particularly harmful to attribute the changes to the individual members of the committee who have collaborated with the fossil fuel industry, thereby suggesting that they have allowed their own interests to prevail."

In addition, the university board changed a “demonstrable” effort to find a sustainable partner to a “reasonable” effort, because otherwise it would not be “practicable” in practice. According to the board, choosing a partner for projects is “complex” because some companies do not want to collaborate with each other or only want to participate if a certain company is involved. The UU therefore wants scientists to make a reasonable effort to explore sustainable partners, but does not consider it desirable that this should be demonstrated.

Reliable partner

Wilco Hazeleger was dean of the Faculty of Geosciences when the framework was drawn up. He explains why he asked for an exception to existing consortia at the time. He felt it was important to convey the different views within his faculty during the consultation with the deans. “There is a very activist side that wants to stop everything, but there are also researchers who say that we need to work with fossil fuel companies to make the energy and materials transition. As dean, I indicated what my constituents felt.”

As rector, Hazeleger also emphasises the importance of being a reliable partner. He fears damage to the university's reputation if it refuses to participate in new projects in existing consortia. In addition to the fossil fuel industry, the UU works with other Dutch universities and government agencies, such as the Ministry of Economic Affairs, NWO and TNO, in these consortia. “These are usually consortia that are already fully operational and have agreements in place. For new projects, we still look at the content to see whether they are working on the energy transition. The subsidy provider often requires the fossil fuel industry to be an external party in the consortium. We may have all kinds of moral objections to this, but in principle the existing consortia work well and we intend to continue with them.”

He does not want the UU to lose its credibility “in the broader, larger world in which we operate and conduct research. The existing consortia will eventually come to an end. We are participating in the programmes. New projects are sometimes started within them, but eventually we will slowly but surely phase out.”

According to Hazeleger, money did not play a role in the decision to exclude the existing consortia from the assessment framework. The UU receives a total of 33 million from the consortia in which the fossil fuel industry participates. The faculties of Geosciences and Science receive the largest share. "It's not about money. It's really about the content. Of course, it's annoying when money is lost, but these amounts are not dominant in the faculties' budgets. The argument was that the framework had to be workable and that the university must remain a reliable partner. A large group of scientists at the UU are convinced that we need to work with large parties to make the energy transition. Unfortunately, these are fossil fuel companies."

Illustratie: S4F

Disgrace

Guus Dix of S4F says that this is “even worse than I could have imagined”. S4F also considers the original assessment framework to be weak. "Interested scientists were first allowed to participate in the open dialogues, then given a prominent place in the committee that drew up the assessment framework, and were able to exert influence a third time through their deans. The fact that the Executive Board gave deans the opportunity to further weaken an already weak draft proposal shows that fossil fuel interests ultimately continue to prevail at UU.

“I find it extremely sad that the current rector played a leading role in this disgrace. And it is unworthy of a climate scientist to remain in the Sustainable Industry Lab alongside BP, Shell and ExxonMobil.”

The committee that drew up the assessment framework consisted of eight scientists, four of whom work or have worked with the fossil fuel industry. Three of them are or were members of a consortium with a fossil fuel company. Shell funded the research of one of these three. At the time the committee was working on the framework, the fourth researcher was director of the think tank Sustainable Industry Lab, which includes another committee member and Rector Hazeleger. This partnership to accelerate the transition of industry has more than fifty participants. These include scientists, people from the business community (including the fossil fuel industry), government agencies and environmental organisations.