Internationals surprised and worried after Dutch elections

‘I feel like a second-class citizen’

Similarly to their counterparts at other Dutch universities, UU students and staff have come to see the Netherlands with less rose-coloured glasses since their arrival. In the joint survey conducted by DUB and other university media, a quarter of the 294 respondents from Utrecht University went from feeling “totally welcome” or “more or less welcome” to “neutral”, “more or less unwelcome” or “totally unwelcome”. The political situation was mentioned by roughly 20 percent of UU respondents as a reason for not feeling as welcome anymore.

Many UU students and staff members are still feeling the shockwaves of PVV’s victory in the Dutch elections, especially considering that Utrecht is a left-wing stronghold and over 50 percent of votes cast at the polling stations located inside Utrecht University’s buildings went for GroenLinks-PvdA (an alliance between the Green Left and the Workers’ Party, Ed.). Best known for his anti-immigration rhetoric, PVV’s leader Geert Wilders would like all Bachelor’s programmes in the Netherlands to be offered in Dutch. If it were up to him, Europeans would need a visa to study here and they would not be entitled to study financing.

A lot is still up in the air, however. If Wilders manages to form a coalition, it remains to be seen to what extent he will get his way. Besides, for a U-turn on internationalisation to take effect, the future Minister of Education must first submit a bill to the approval of the Parliament and the Senate. But, for international students and staff, the fact that a significant chunk of Dutch citizens chose to vote for PVV is reason enough to feel even less welcome and worried about the future.

"Even though I try hard to integrate and assimilate, I’m still not wanted"

Theodora, who studies History, is one of the people who feels less welcome now compared to when she first arrived. She comes from Indonesia and fears that the Indonesian community in the Netherlands will be discriminated against, despite Wilders’ grandmother being of half-Indonesian descent, a fact he doesn’t discuss much.

She says Wilders doesn’t have a very good reputation in her country of origin. In 2008, for example, the Indonesian government ordered the nation’s Internet providers to prevent customers from accessing a video of an anti-Islam speech by the Dutch politician. 87 percent of the Indonesian population identifies as Muslim. “I am not Muslim myself, I’m Catholic, but some of the nicest people I know are Muslims and I’m afraid they will suffer because of a few bad apples,” she says.

Theodora plans to stay in the Netherlands after her degree. First, because she would like to research the colonial period in Indonesia and the subsequent relationship between the Netherlands and Indonesia. Secondly, because she is in a relationship with a Dutch person. “Our plan was for me to stay here, but if the cabinet starts enacting harsh immigration policies, maybe we will have to think of something else.”

That would mean reconsidering everything. “All my plans revolve around staying here for my Master’s and maybe a PhD. I am not even sure if my degree would be accepted in Indonesia. This is really frustrating. Even though I try so hard to integrate, assimilate and learn the language, it still feels like I’m not wanted here.”

"Statistically, there must be some people here who voted for him. Which of my colleagues is it?"

Linda* is an assistant professor at the Faculty of Geosciences. She moved from the UK to the Netherlands in 2009. When she first came here, she thought the place was “great”. People were friendly and spoke English to her, so she didn’t feel bad for not speaking Dutch before her move. “But the longer I stayed here, the more things happened that made me feel more and more uncomfortable.”

The most emblematic example she can remember is when she was pulled out of a first-year Bachelor’s course she was teaching, after working three to four weeks full-time on its preparation. “There was this massive fuss that no first-year courses should be English-taught. They kept saying: ‘It’s not personal’ but of course, it felt personal after putting in all that work. The students were getting a good education and their exam results were good. Isn’t that what’s supposed to matter?”

Even though she’s been here for so long and has obtained the highest proficiency diploma for non-native Dutch speakers, she still feels like a second-class citizen. To her, the main issue isn’t so much feeling welcome as feeling valued. “I feel like people don’t mind me existing. They’re happy for me to work at the university, but I would be more valued if I were Dutch.” Speaking Dutch didn’t make it easier to befriend the Dutch, either. “Dutch people have their lives and they go home at 5:00 ‘o clock. It’s always been difficult to integrate.” To this day, most of Linda’s friends are fellow internationals.

Geert Wilder’s victory was a wake-up call for her. “I’ve encountered people outside the university that gave me the impression that they don’t like foreigners being here. But I always told myself: ‘It’s only a few people who think like that.’ After the elections, I was like: ‘OK, this is a bigger problem than I thought.’” She is happy that PVV doesn’t have a massive following in Utrecht. “But 10 percent of Utrecht-based voters voted for him, so sometimes I’m at work and I’m thinking: ‘Statistically, there must be some people here who voted for him. Which of my colleagues is it?’”

Linda is not planning on moving out just yet, although she wouldn’t discard a good opportunity elsewhere. “I am not anchored to the Netherlands. But if you’re going to leave, you’ve got to have somewhere better to go. The UK is… complicated right now. And I think most countries nearby are having the same kind of problems as the Netherlands.”

*Linda is a fictitious name. The UU employee asked DUB not to use her real name in the article, although she doesn’t mind her position and faculty being mentioned.

"I’m more aware that people might see me as part of the problem"

Lara-Marie comes from Germany and studies Sustainable Development. She is one of the students who felt welcome before the elections but started changing her mind once she saw candidates promising policies to lower the number of international students.

She was caught by surprise by Wilders’ landslide victory. “I just didn’t expect it to happen here, the country seems so open-minded. I talked to some of my Dutch friends because I thought maybe I was just naïve but they were just as surprised as I was. I guess we were living in a bubble.” The election results were an eye-opener for her. “I started seeing myself as a foreigner too. Before, I never really considered what that could mean. Now, I am more aware that people might see me as part of the problem.”

A day or two after the election results, she overheard two neighbours complaining in the hallway about the number of international students and how they hardly ever heard Dutch being spoken in the building anymore. “I didn’t know those people or the context of their conversation but I automatically perceived it as negative because I’m more aware of my position in this country now.”

She is nervous about what the future has in store for foreigners. “Not necessarily for myself because I can pack my things and leave. It’s heartbreaking that there are people who have lived here for generations and are now made to feel like they don’t belong here.”

"This country was supposed to be more open-minded than others"

Emma is a first-year Geosciences student from Greece to whom the Netherlands has been a bit astonishing so far. One of the reasons that led her to study here was the country’s fame of being more tolerant and open-minded than others. “I wouldn’t study in Hungary, for example.”

She definitely wasn’t expecting it to be so hard to connect with the locals. “When I first got into the classroom, it was divided in two. All the Dutch people were sitting on the right side and all the internationals were on the left. They are always speaking Dutch with each other, despite the programme being in English, and many of them don’t say hello or goodbye to their international classmates.”

She stresses that this is not a matter of language barrier, since her Dutch classmates speak English too. “It’s more of an attitude,” she says, although she can’t yet pinpoint what it is that makes them act this way. “This might be a cultural characteristic. I’m not saying they are bad people.”

PVV’s victory in the elections was another big surprise for her, even though she had been following the news about Parliament discussions on internationalisation and the housing crisis. “But I never expected this to be the result. The Dutch people I’ve talked to about this don’t seem to understand it either. How come?”

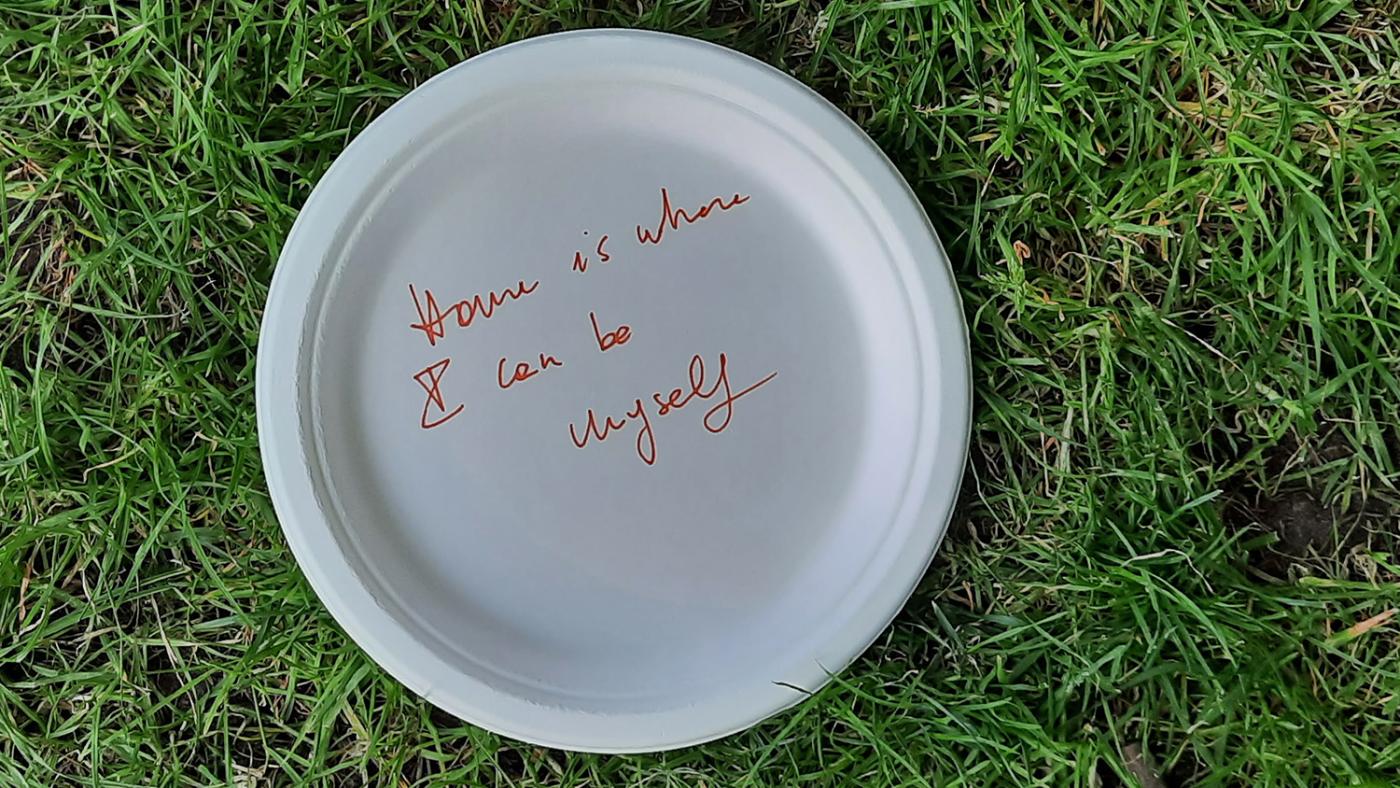

International students enjoy a barbecue organised by UU in partnership with ESN and Buddy Go Dutch. During the event, students were asked to share how welcome they felt. Photo: DUB

Speaking of the housing crisis, she has seen many comments online from Dutch students telling their international counterparts to go home and leave student rooms for the locals. She finds those comments annoying. “The Netherlands created this issue themselves. They wanted internationals to study here, that’s why their programmes are like this. They needed workers from other countries to support their industries. They created the housing problem. It’s not the internationals’ fault.”

She fears what the future may hold for foreigners, but, at the same time, she does not think she is the main target. “People who are not highly educated are more susceptible to hostilities.”

Like Linda, Emma sometimes catches herself wondering if people around her voted for PVV. “Sometimes, when I speak English to someone at the grocery store or public transport, I get a thought at the back of my head: ‘Did this lady vote for a far-right party? If so, what is she thinking right now?’”

Despite these disappointments, Emma does see herself working here after graduating. “At the same time, do I want to live in a country that is so conservative?”