Debate organised by Utrecht Young Academy delves into the dilemma

Why, how and when to use English in academia?

Dutch universities should be multilingual, but it is also their role to make sure that Dutch does not disappear as an academic language. They should also provide their numerous international academics with time and resources to learn and practice Dutch, regardless of the type of contract they hold. Meanwhile, their Dutch colleagues should bear in mind that acquiring a new language takes time. Finally, research should be accessible to society at large – and this principle should guide not only the choice of language but also the terms and jargon used. These were the main takeaways of an event organised by the Utrecht Young Academy on April 5.

Although the use of English in academia has become a recurrent topic in Dutch politics and the association of Dutch universities (UNL) is making plans to anticipate political decisions in this regard, the Young Academy finds that the topic is not being sufficiently discussed on the work floor. “These decisions will affect all of us and what we do in our professional and student lives,” states the platform for young researchers. Hence the decision to hold an event where students and staff members could share their thoughts and experiences.

About thirty people gathered in the Administration Building to watch a panel discussion with Patience Gondwe, Policy Advisor for Internationalisation at UU; René Gabriëls, a philosopher from Maastricht University and co-editor of The Englishisation of Higher Education; Goffe Jensma, Emeritus Professor of Frisian at Groningen University; Pepijne van Rooijen, Master’s student of History of Politics & Society and student assessor at the Faculty of Humanities; and Verena Seibel, Assistant Professor in Integration and Migration Studies at UU.

Some of the panellists preferred to speak English, while others preferred Dutch. They all understood each other without any problems, so the debate went smoothly. However, those in the audience who did not speak Dutch at an advanced level, such as a teacher from Greece, struggled to follow and missed out on some of the arguments. While passionately arguing that Dutch is under threat, Gabriëls used a few English terms that do have equivalents in Dutch, such as “Dit is een social justice issue”. This goes to show the extent to which the two languages are intertwined in Dutch academia.

The Young Academy asked the panellists to react to several statements that are commonly made in the debate regarding language use in Dutch academia. Here is what they said about some of them.

Bachelor’s taught in Dutch, Master’s taught in English: the best of both worlds?

Earlier this year, UNL announced that all “major” Bachelor’s programmes offered only in English would get Dutch-taught tracks as well. There seems to be a consensus that most Bachelor’s degrees should be taught in Dutch, while a significant number of Master's programmes should be available in English. Is that a good idea, though?

Student assessor Van Rooijen enjoyed doing her Bachelor’s in Dutch and her Master’s in English, as she had the opportunity to improve her academic writing in both languages. However, she argues that this might be different for other students and it isn’t a one-size-fits-all case. She also stressed how it has been a growing experience for her to get in touch with other perspectives in her Master’s. She thinks the international classroom is of great added value to students' learning experience.

Maastricht University Philosopher Gabriëls believes that both languages should be present both at the Bachelor’s and the Master’s levels. However, Dutch should account for 60 percent of all courses and English for 40 percent. “Most students choose a programme in English due to career expectations, but Dutch must not disappear as an academic language. To do that, you must offer it at the Master’s level too.”

Groningen Emeritus Professor Jensma agreed with Gabriëls and added that one should not only consider which language to teach in, but also how well students speak English or Dutch. This can vary from student to student, noted UU Assistant Professor Seibel: students from non-academic backgrounds tend to have a harder time speaking English than wealthier students from academically-educated families.

Photo: DUB

Is English the language of science?

“Yes and no,” said UU Policy Advisor Gondwe. In her view, English as a language of instruction and publication is a convention that happened organically and is subject to change. “We shouldn’t want to formalise this.” She believes that Artificial Intelligence could facilitate multilingualism in the future. “The technology will only get better.”

Seibel observed that other countries, such as her native Germany and France, are very protective of their languages. But, in her view, that is a shame. “I don’t know what’s going on in France. So, we’re constantly reinventing the wheel. Publishing in English allows us to understand each other.”

Gabriëls underscored that a choice of language also means a choice of topic. When publishing in international journals becomes crucial for a scientist’s career, their research topic needs to be interesting for an English-speaking audience. “That’s how local questions end up put in the backburner.” In his opinion, many publishers are short-sighted. “They will reject an article about food banks in the Netherlands, for example, deeming it too local. But the findings could be useful for other countries to know.”

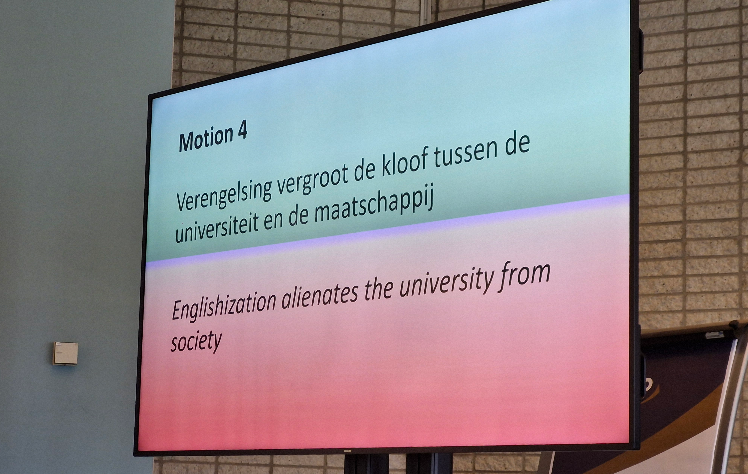

Does Englishisation alienate the university from society?

“Scientists aren’t reaching everyone in society because of the type of language they use in their publications. It’s not an accessible language for everyone, regardless of whether it’s in English or Dutch,” remarked student Van Rooijen.

Gabriëls finds that the anglicisation of higher education only has the interests of academics in mind, not the interests of society at large. He argues that publishing in English only widens the divide between academia and the general population. “English doesn’t have a total coverage,” Gondwe agreed. “It might have in the education sector, but not among people in general. So, how can science reach people and not just their peers? That’s what should be taken into account when choosing a language to publish.”

Jensma reacted by saying that, unfortunately, things are not that simple because scientists work within a system. To have a successful career, most researchers are forced to publish in English. Some members of the audience pointed out that it is possible to publish in both languages, but Gabriëls and Jensma retorted that the number of academic articles in Dutch has diminished in recent years, with certain journals even ceasing to operate altogether.

In addition, Gabriëls said that being able to speak Dutch allows him to popularise science by writing op-eds for Dutch newspapers. But Seibel noted that foreign scientists working in the Netherlands can do the same – and they have – even when their Dutch isn’t perfect. According to her, certain newspapers are willing to translate op-eds from English to Dutch if the content is deemed relevant enough. Some TV channels will also add subtitles when interviewing international academics.

No either-or situation

After the debate, the audience was invited to contribute to the discussion as well. Several well-known faces could be spotted among them, such as Jan Ten Thije, Emeritus Professor of Intercultural Communication; Rick de Graaf, Professor of Foreign Language Education and Bilingual Education; Mia You, Assistant Professor of English Language & Culture; and Matias Edelstein, one of the international students in the UU Council.

Rick De Graaf raised his hand to stress that this is not an either-or situation. “There are many possibilities. We could work in combination. Subtitles and luistertaal are just two of the solutions implemented by the UU Council, for example. But it doesn’t happen automatically. We need to research the best ways to do it and stimulate internationals to learn receptive Dutch, which is easier to acquire than speaking.” However, he noted that UU outsourced the James Boswell Institute, which used to facilitate this.